Special Report: Without A Name

FALFURRIAS - Volunteer groups are working to identify hundreds, possibly thousands of unidentified bodies buried across South Texas. They are presumed migrants with no names, no stories and usually no grave markers.

As per Texas law, unidentified remains are required to be investigated. It mandates DNA samples be taken and put into a database before the remains are buried. It also states precise documentation must be kept for the locations of the burials.

CHANNEL 5 NEWS’ investigation revealed those law aren’t always followed in the Rio Grande Valley, leaving many people buried without a name.

Volunteers at Sacred Heart Cemetery in Falfurrias dig for unidentified remains buried without any scientific analysis and without a change of identification. They examine the bodies and take DNA samples.

University of Indianapolis associate professor of biology and anthrophony Krista Lathan said she returned to Brooks County in January for her third dig.

“We thought we were coming to excavate maybe 10 burials… We now have 24,” she said.

Lathan and her students helped exhume close to 200 sets of human remains in 2013 and 2014. They thought their trip on January would be their last one in Brooks County, until groundskeepers pointed out more areas where unidentified remains are buried without a grave marker.

“It does look like we’re going to have to come back another year, because we’re going to have to investigate all those areas that were pointed out to us,” she said. “We’re also going to do systematic searches of the cemetery to see if there are any other unidentified markers that are randomly scattered in the cemetery in places that no one had looked before.”

Texas State University students helped with the dirty work. They used ground-penetrating radars to locate remains and treated graves like an archaeological dig.

After they pulled remains out of the graves, students went straight into tents where researches inspect body bags and separate personal effects from bodies to gather as much information as they can.

Unfortunately, sometimes the body bags give few details about the person inside.

The real identification process starts at Texas State University, located 200 miles north of Brooks County.

“Right now, they are sadly just a case number. And our goal in analyzing all these presumed migrants is to figure out who they are and instead of them being a number, give them their name back,” Tim Gocha, postdoctoral research fellow at Texas State, said.

Gocha leads the team tasked with analyzing remains. The team cleans the skeletons with care and thoroughness, and lays them out to be studied.

In one instance, they found bones in an unmarked grave that belonged to the youngest person they’ve exhumed in Brooks County, a child of 11 to 14 years old.

Gocha said all remains will be analyzed to find a likely country of origin, time of death, sex and age.

So far, the forensic team identified 21 people. He said the recoveries give family members a chance to pay their last respect and bury their loves ones with dignity.

“It’s very humbling sometimes working with them, and seeing the grief and the loss on their faces. At the same time it is – on some level, rewarding – because you’re able to give them that sense of knowing, rather than their loves one just being missing somewhere in South Texas. It allows them a sense of closure,” Gocha said.

More than 200 presumed migrants sit in boxes waiting to be identified. Their bags contain small clues to their identities such as clothing, ID’s and small tokens from their home country.

However, researchers estimate there are still hundreds more buried in cemeteries all across the Rio Grande Valley.

“The sad reality is how many individuals might be out there who haven’t even been found yet,” Gocha said.

Gocha showed us maps of other cemeteries across South Texas. He said unidentified bodies are buried in those locations also. His team goes county to county, mapping out spots that will eventually have to be exhumed.

“This problem is not just in Brooks County. It’s very widespread. It’s all over South Texas,” Texas State associate professor of anthropology Kate Spradley said.

Spradley said they’ve found at least 130 burials in Starr, Brooks, Hidalgo, Jim Hogg, Cameron, Willacy and Kenedy Counties.

“There are hundreds more that will never be recovered, maybe even thousands,” she said.

The state of Texas laid out how counties should deal with unidentified remains. However, Spradley said each county goes about it differently.

“Sometimes it is following the Texas Code of Criminal Procedures, sometimes it arbitrarily follows the Texas Code of Criminal Procedures and sometimes it does not follow it at all. So, each county is unique in the way that they handle unidentified human remains,” she said.

One law does require counties to “collect samples from unidentified human remains.” The DNA samples can then be entered into national databases. Another law lists medical examination procedures that could easily be performed by a medical examiner or forensic anthropologist.

One of the requirements lists there should also be precise documentation of the location where remains are buried. However, it’s a requirement every county in the Rio Grande Valley has failed to do so in the past.

Spradley said some are still failing to do so today. She said that’s what makes her mission to map out unidentified remains a daunting task.

“It’s been extremely difficult. There’s no paper trail and it’s usually memory recall. It’s usually someone from a funeral home or an autopsy technician or death investigator that has to take us and show us where individuals are buried,” she said.

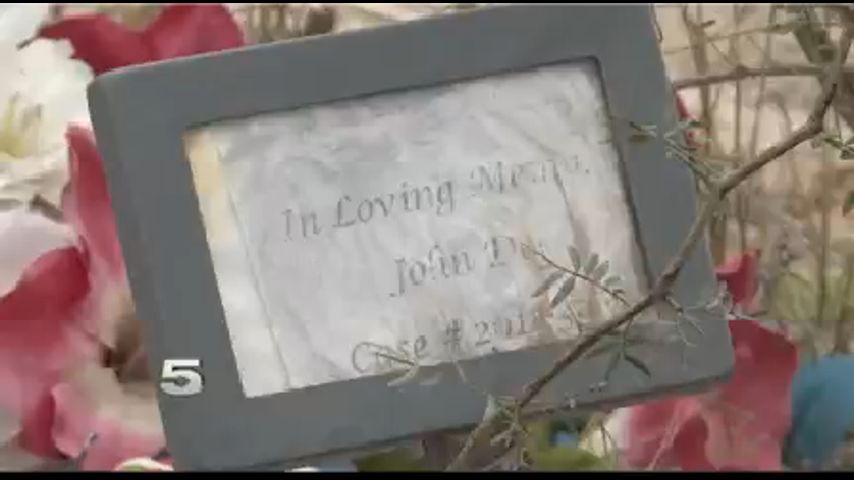

In Starr County, markers are rarely placed on the sites where remains were buried. A simple piece of paper with the words “John Doe” sits on the ground protected with plastic and aluminum.

Rio Grande City's cemetery only has one marked unknown grave.

South Texas Human Rights Center director Eddie Canales said he’s also helping in the cemetery mapping effort. He showed us unmarked plots where unidentified bodies are buried.

He said a rise in the ground usually indicates there’s a body below. The cemetery’s groundskeeper, Andres Lopez, also showed Canales and Spradley sections where he remembers burying John and Jane Does.

Lopez has lived next to the cemetery for more than 50 years. He estimated there to be around 100 possible bodies buried in the area. He recalled many of those were buried under mysterious circumstances.

“They found a body one time, some years back, without a head. They did a very serious investigation on it,” he said.

Canales said he hopes to get permission from Starr County to do exhumations in the cemetery. But he said getting funeral services and cemeteries to cooperate with their mission is difficult.

“In Brownsville, one of the cemeteries is supposed to have 100 or more. We’re told we can’t even see them. We can’t see the burial site. (It’s) kind of odd,” he said.

The number of bodies can be a burden to some counties with limited budget and resources. The Brooks County Sheriff’s Office said their body book is a humbling reminder of how serious the problem is.

Brooks County Sheriff Benny Martinez said his county now has a protocol, adherent to the law, when it comes to unknown remains. He said he expects the county to deal with the issue for as long as people continue to cross the border illegally.

“It just needs to be stopped. Period. Something needs to be in place where this doesn’t happen anywhere on the southwest corridor,” he said.

Volunteers and researchers said they hope other counties follow Brooks County’s lead. They want the state to enforce the laws already in place and give people some dignity by the time of their deaths.

“The state of Texas should probably take these cases a little bit more seriously than just assuming they’re all migrants, and burying them without identification efforts,” Gocha said. “Clean up all the dust so that it’s a smooth surface that we can take a photo and take some coordinates on.”

The cemetery mapping team will investigate all Texas counties. They plan to continue their efforts along the border and spread to the rest of the state.

The group hopes more local officials, state lawmakers, cemeteries and funeral homes will join their cause and make sure no one is buried without a name.

Links for Reference: